For a country with one of the world’s highest rates of species extinction, Australia received some rare, good news last week.

After 60 years of protection, humpback whales have been taken off the Australian threatened species list. Federal Environment Minister, Sussan Ley announced the decision. “Our removal of the humpback from the threatened species list is based on science and sends a clear signal about what can be achieved through coordinated action. It is a message of hope for the welfare of a number of species.”

… their population has gone from just 1500 animals off the Australian coast to an estimated number today of 40,000.

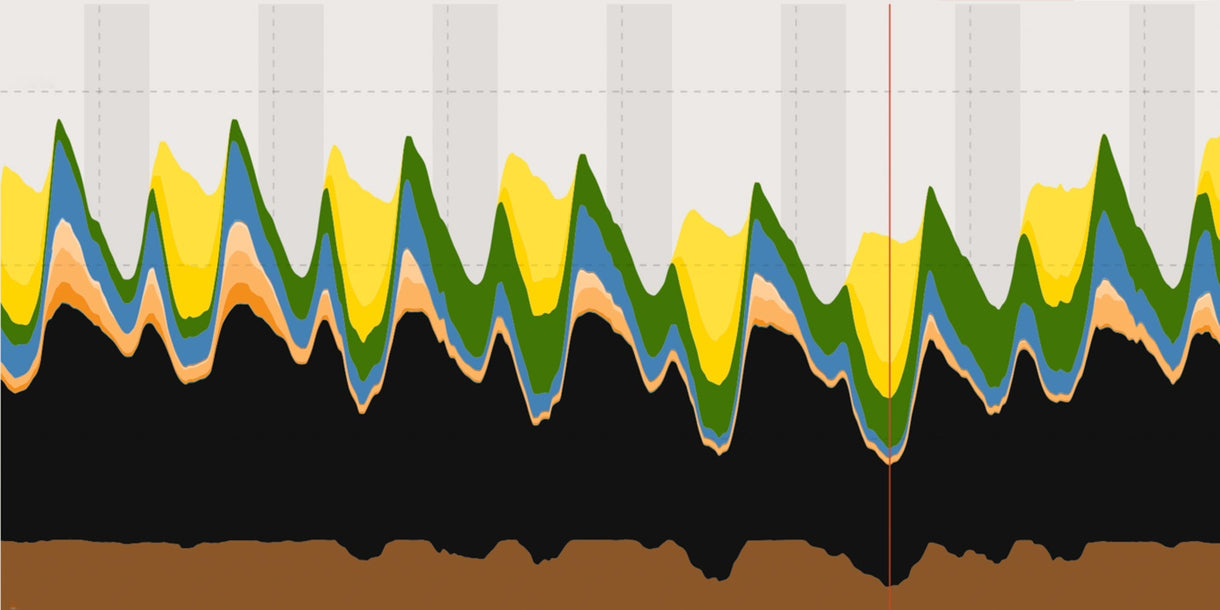

The rebounding of the humpback populations off the east and west coast of Australia has been nothing short of remarkable. In the space of a humpback lifetime, their population has gone from just 1500 animals off the Australian coast to an estimated number today of 40,000.

The last commercial whaling operation in Australia – at Cheyne’s Beach outside Albany, West Australia – closed in 1978. The last commercial whaling on the east coast ended in 1962, with just a few hundred humpbacks left in the local population. Ironically, the last two east coast whaling stations to close were at Tangalooma and Byron Bay, both of which today are home to thriving whale watching tourist businesses.

Since the end of commercial whaling, the humpback populations have increased at staggering rates. It’s believed Australia’s west coast humpback population is currently increasing at 9% per year, while the east coast population is increasing at 10% annually. These are the highest rates of humpback recovery anywhere in the world. Theories as to how the Australian populations have rebounded include prime breeding grounds inside the Great Barrier Reef allowing humpbacks to breed at twice the rate of humpbacks breeding out in the South Pacific.

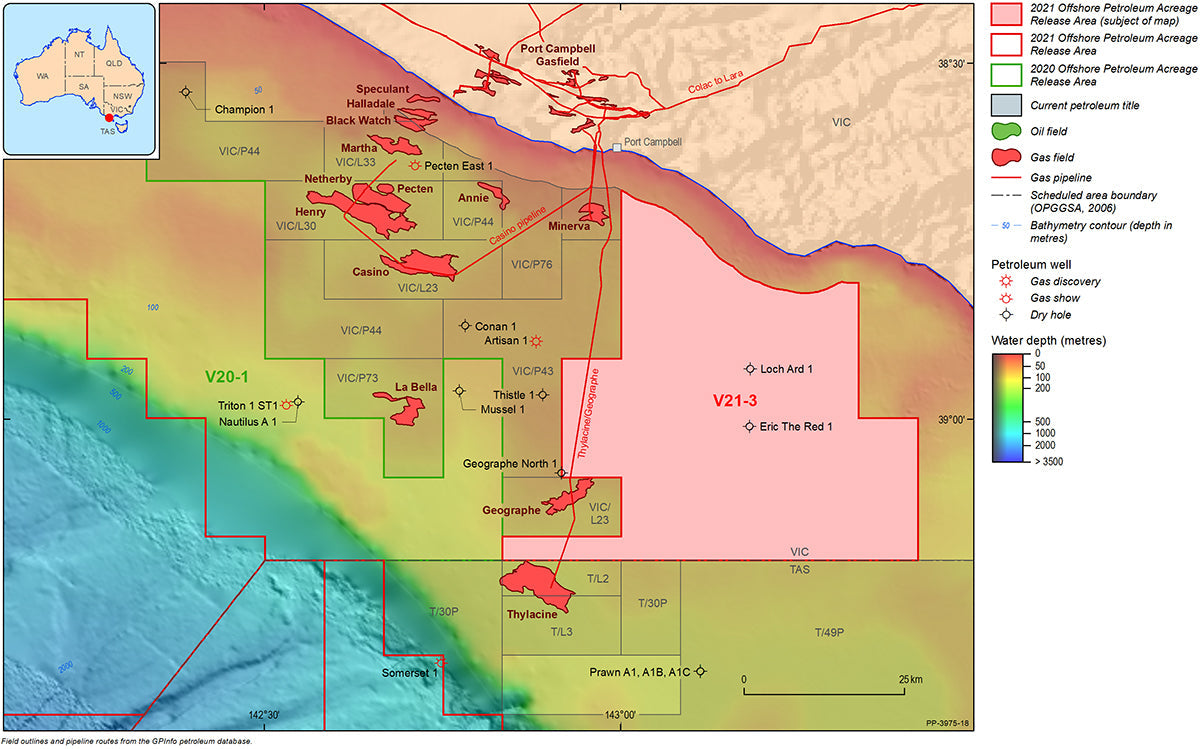

But while the rebounding humpback population is great news, it comes with a sobering caveat. Scientists have warned that the effect of climate change on the whales feeding grounds in Antarctica could see populations threatened in the near future. Already there are signs that changing climate and water temperatures are affecting humpback migrations. There are also a number of ongoing threats, including overfishing of krill, seismic testing by the petroleum industry, collisions with ships and entanglements in shark nets.

Maybe the more sobering news however is that the speed of the humpback’s recovery hasn’t been shared by other Australian whale species. The Australian population of southern right whales for instance are increasing by almost 7% annually, but with a much smaller total population of just 3500 individuals.

Image Banner: You're not mistaken if you think the annual humpback migration has been getting busier in recent years. Photo Jarrah Lynch

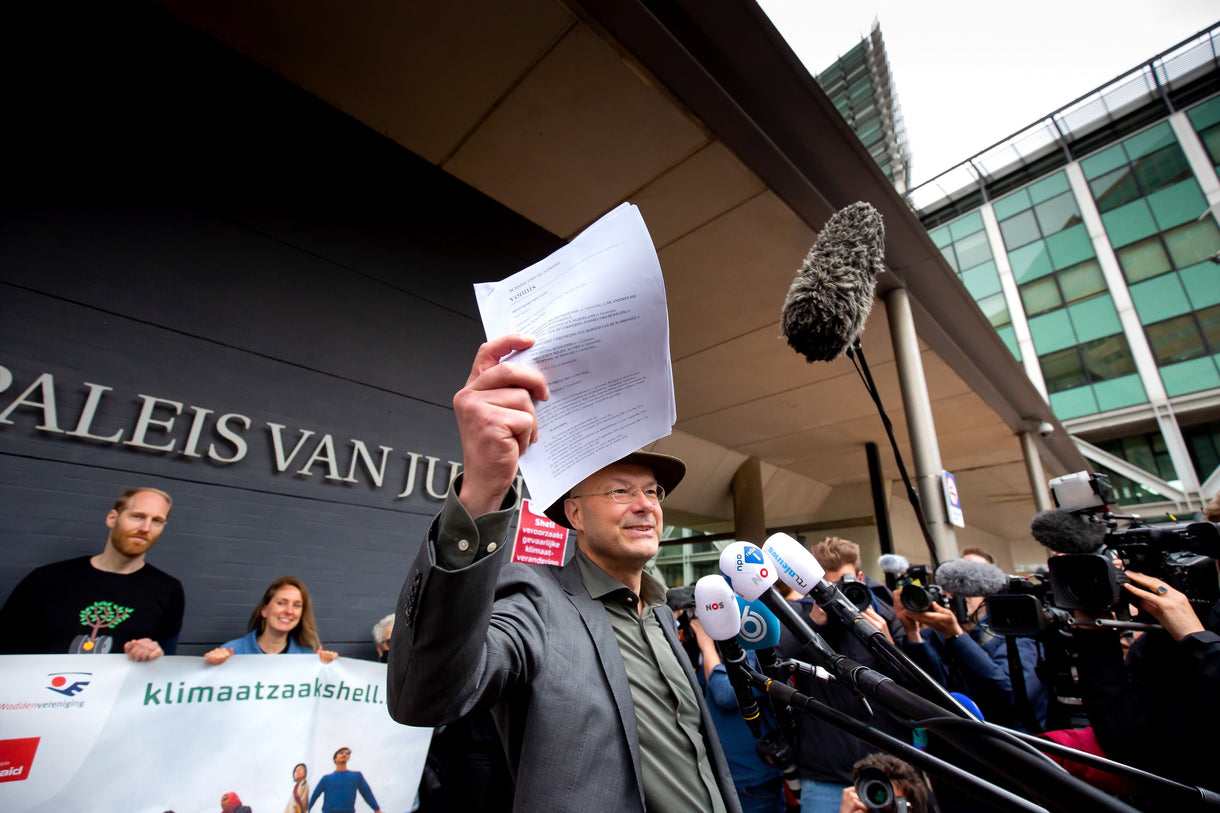

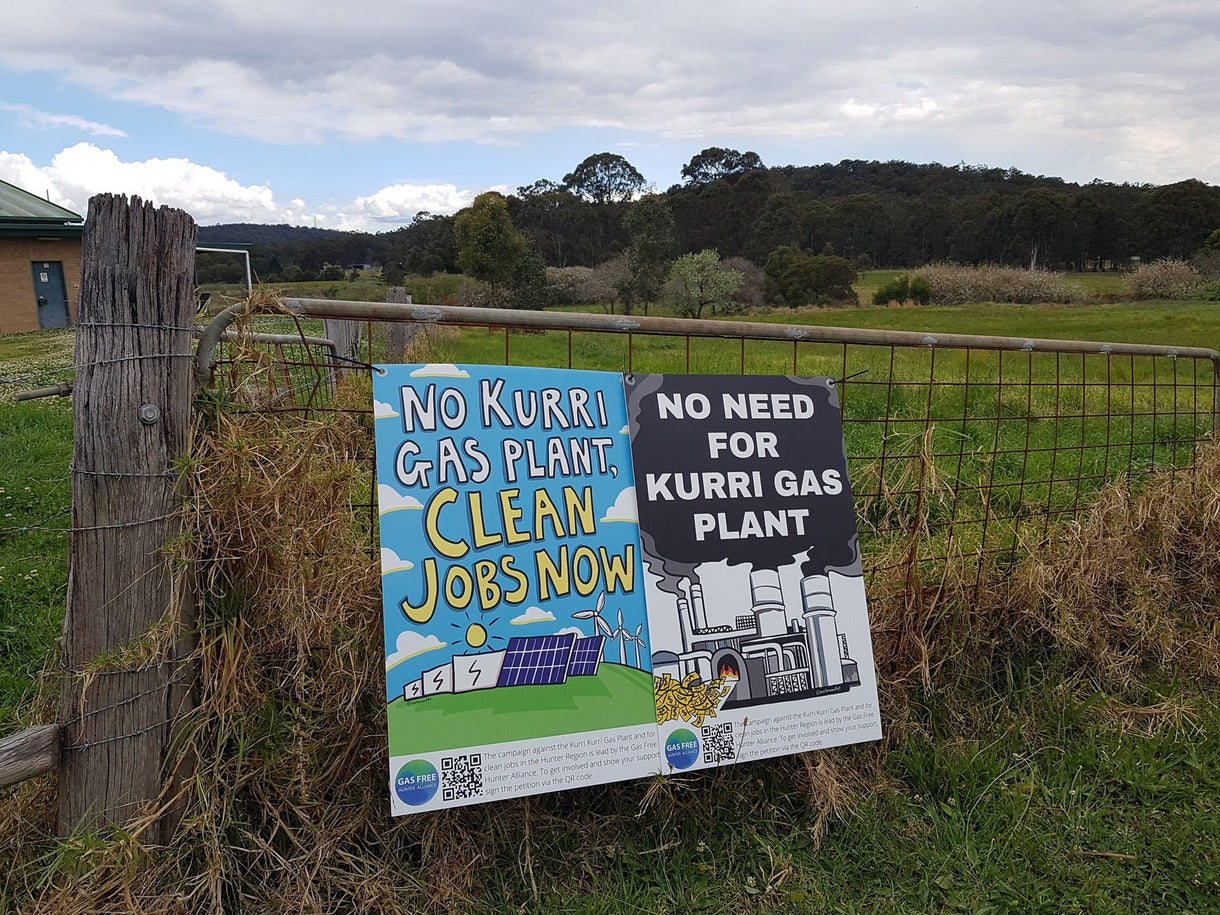

![Today was a huge victory for coastal communities between Sydney and Newcastle. [Front] Damien Cole, Belinda Baggs, Drew McPherson and Asha Niddrie. Photo Zoe Strapp](http://www.patagonia.com.au/cdn/shop/articles/strapp_z_AUS_000142_b147f38f-4f28-4e66-a3ea-89fccd422484_1220x.jpg?v=1650419749)