Their depth of character becomes evident as we weave ourselves into their lives and ecosystems. But we often tell our stories and not theirs. Our new film Treeline follows skiers and snowboarders as they move through three extraordinary forest landscapes across Japan, British Columbia, and Nevada, exploring the connection between humans and our oldest living companions. This essay is part one of a four-part series.

Trees are intertwined with human existence—through religion, in times of war, in standing for what we’ll fight to protect, with our hopes and wishes that we share. They stand implanted in our own history. There’s a whole world of legendary trunks out there, like the Bodhi Tree in India—the canopy under which Prince Siddhartha transformed into the Buddha. The Wishing Tree in Portland, Oregon—a horse chestnut that boasts the written hopes of both locals and visitors, who tie notecards to its branches until they’re whisked away by wind and rain. The Hiroshima Bonsai, one of the oldest bonsai in the world, that survived the atomic bomb in a nursery just two miles from the epicenter. Luna, the coastal redwood that Julia Butterfly Hill occupied for 738 days starting in 1997 to protect her from being cut by the Pacific Lumber Company.*

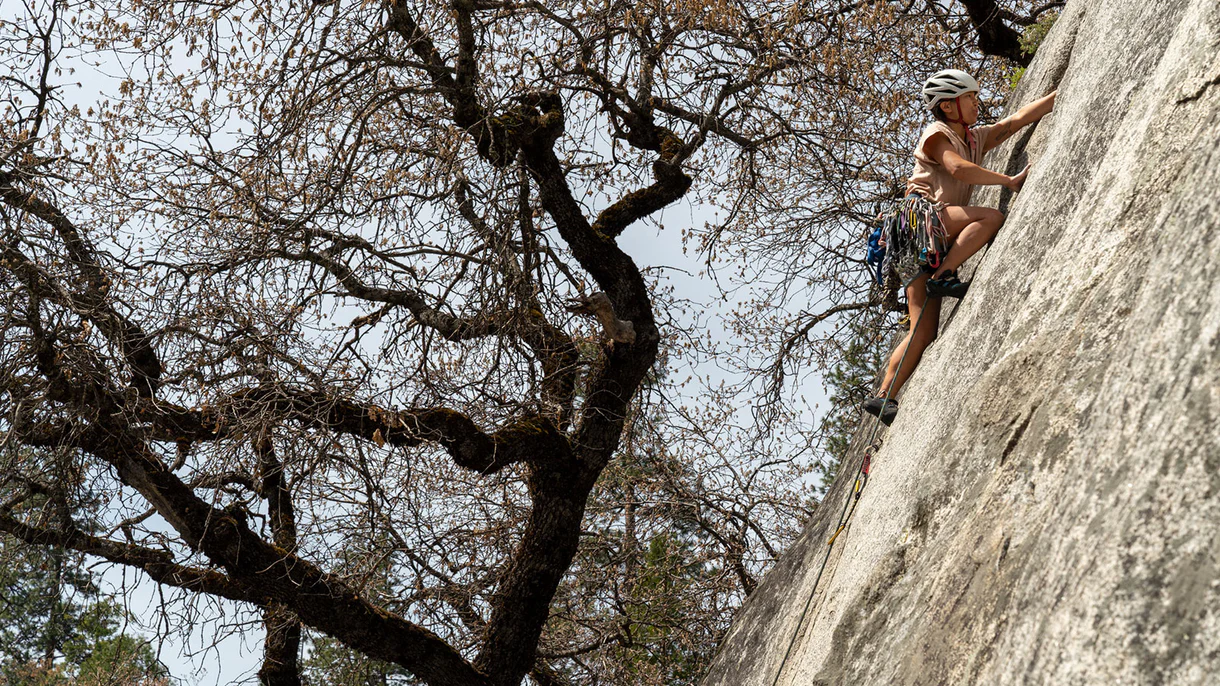

Alex Yoder rides the line in a secret spot outside Niseko. Hokkaido, Japan. Photo: Garrett Grove

But a tree can’t vocalize or write itself into our records: We must assign them importance, even though they always stand taller, grander, and very often, longer than us. There’s a necessary humility that arises from simply noticing our barked, gnarled and rooted companions.

When we travel in winter through the forest, we are passing through the trees’ homes and communities, weaving ourselves into their lives and ecosystems, but we often tell our stories and not theirs. What about the intersection of us and the trees? Is it enough just to recognize that they’re there? Does this gesture make us a symbiont of the woody tribe?

Snowboarding or skiing through the trees is a lifeline, providing refuge for winter days when the alpine snowpack is sketchy. It’s pure joy. It’s powdery cruising in December when it’s dark at 3:30 p.m. and you’ve had your hood up all day—hooting and hollering through birch, spruce, cedar, and pine—finding pillows to launch along the way. Forests can be a giddy, expansive playground and serious haven of safety, both at the same time. When we ride through a forest, we have a fleeting opportunity to notice how trees influence us, to understand how they redefine our own winter-loving lives.

*From Wise Trees, by Diane Cook and Len Jenshel, 2017, Abrams, New York.

Treeline film- tour coming soon.