All photos by Tim Davis

When I begged my daughter to surf with me last spring, I thought I knew what I was after. I’d grown up climbing with my own father in Yosemite and learned to surf from an uncle in north San Diego County, California, so I’d always wanted my kids to share the mountains and waves with me in the same spirit.

In the mountain department, Hannah, the older of my two daughters, became the best climbing partner a dad could hope for and even took the sharp end on old-school Yosemite fistfights like Selaginella and Higher Cathedral Spire.

In the ocean, I’d been less successful. San Francisco, where we lived, had such frigid water and violent swells that my girls weren’t interested. There was a beginner’s break 20 minutes south called Linda Mar, but it filled up with dense crowds of adult novices wiping out together on mass-market pop-out longboards – I couldn’t see how anybody had fun out there.

My attitude wasn’t always this bad. Back in my 20s, I lived in Santa Cruz and surfed year-round – juicy winter point breaks on step-ups, springtime slop on “skatey” fat thrusters, sunny summer ankle-slappers on a weird old twin-fin longboard. I’d even surf Steamer Lane and Pleasure Point, where the surfing hordes get thicker than mosquitos in Alaska.

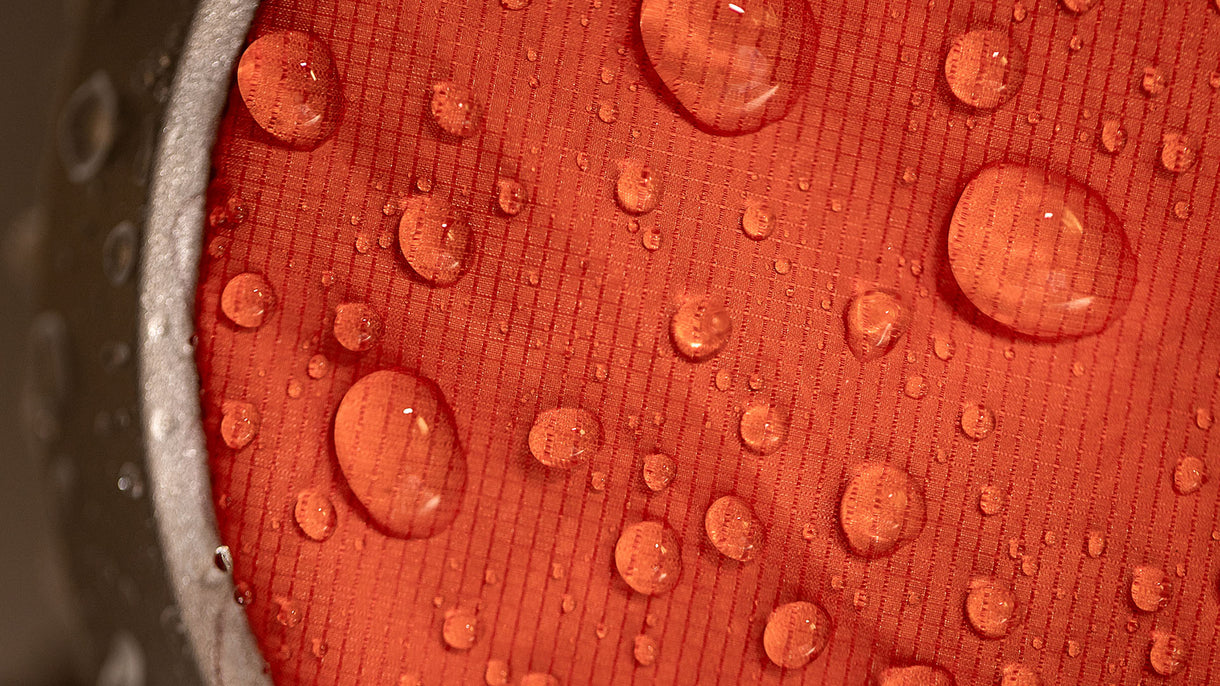

When surf sessions require hoods and booties, finding the motivation to paddle out in small, subpar waves can be challenging. Nevertheless, happiness exists in each rolling wave’s crest if you’ll allow it. All photos by Tim Davis.

When surf sessions require hoods and booties, finding the motivation to paddle out in small, subpar waves can be challenging. Nevertheless, happiness exists in each rolling wave’s crest if you’ll allow it. All photos by Tim Davis.

Over time, though, I’d let myself become that cranky older guy who wouldn’t get wet if the waves weren’t certifiably good and uncrowded – you know, like everything used to be. When I moved to San Francisco, I stopped surfing anywhere but Ocean Beach, that vast and savage stretch of sandbars where punishing whitewater turns the simple act of paddling out into gladiatorial combat and side-shore littoral currents can have you paddling an hour straight just to stay on a peak while outbound rips suck you toward Hawaiʻi.

Ocean Beach gets plenty big and good between October and February, but mostly sucks for the rest of the year. So, I’d fallen into this rhythm of surfing hard in fall and winter, then shelving my wetsuit and sticking with climbing for spring and summer.

Then came the pandemic.

Our Ocean Beach surf season had just ended when COVID-19 forced both my climbing gym and Yosemite National Park to close. The next blow came when Hannah, my number one climbing buddy, left for Deep Springs College on a remote cattle ranch in eastern California. Within weeks, my outdoor-athletic life shriveled to swinging a kettlebell in the park.

Meanwhile, my younger daughter, Audrey, was bored out of her mind taking high-school classes on Zoom and wishing her soccer team still had practice.

One day – or, really, about 20 days in a row – I said something like, “Hey, kiddo, I know I’m always saying this, but I really will take you surfing anytime you want. I mean honestly, I don’t mind. Not one bit. It’s really no trouble. I mean, if you’re psyched and you’d be into it. It’s not the surf season right now, so the waves aren’t great, but I’d be happy to take you down to that Linda Mar place and push you into little peelers.”

Audrey wasn’t having it, so my wife reminded her that, even if she wanted no part in Dad’s suffer-sport silliness, it might be nice to get out of the house.

Get the boards on roof, squeeze into your wetsuit and paddle out there.

Get the boards on roof, squeeze into your wetsuit and paddle out there.

My surfboard quiver had long since shriveled to high-volume guns from esoteric shapers, great for open-water paddling and screaming down the line at Ocean Beach, but not much else. But I still had one longboard, a late-’90s high-performance tragedy with minimal volume and maximal rocker, plus a waterlogged soft top. I strapped both to the roof of the car, told Audrey to buckle her seatbelt and pulled onto the freeway in a mood of such giddy excitement that I kept my mouth shut for fear of traumatising her with fatherly enthusiasm.

Out in the water, among all those hapless beginners in junky two-foot windslop, my number one mission was to convince Audrey that surfing was more fun than anything else. That meant I had to model fun – put out a great vibe, smile warmly at other surfers, push Audrey into waves with a big grin and hoot when Audrey hopped to her feet and rode whitewater to the sand.

After her third or fourth wave, Audrey paddled back out with a big proud smile, and I realised that everyone around us was doing the same thing. Not just smiling, but also hooting for each other, laughing when they wiped out – full of happy excitement over the mere fact of being in the ocean on a surfboard. They were having a great time in the worst and most crowded surf I’d ever permitted myself to be in. And that’s when it hit me: A great time was absolutely available out there, and if I failed to have that good time myself, that was a me problem. The secret to happiness – I mean, no small matter – lay in getting your head screwed on right.

Back on the beach with Audrey, I told her anytime she wanted to go, she could invite any friend and I’d go pick them up and buy them lunch, make sure they had gear and drive them home after. A soccer teammate named Sophie took the bait and slipped into my wife’s old wetsuit. I was just about to push Sophie into her first wave on that waterlogged soft top when Audrey, on the longboard, paddled into an unbroken wave and stood up all by herself for the first time ever. That thrill in Audrey’s eyes – the real deal, known to every surfer everywhere – felt as if I’d finally taught her something useful about how to lead a good life.

Though their teenage daughters don’t like to admit it, sometimes dads have good ideas.

Though their teenage daughters don’t like to admit it, sometimes dads have good ideas.

Sophie was a tough athlete. The next time she joined us, she insisted on paddling herself into waves. Audrey was all about that, gave Sophie the longboard and cheered Sophie on, but floundered on the soft top. That soggy piece of garbage wouldn’t float her. I panicked that Audrey would quit surfing before the hook set. So I dashed into the surf shop right there at the beach and slapped down my credit card for their cheapest longboard, a mass-market 9’6″ epoxy.

Back on the sand, Audrey surprised me by saying she’d rather take turns on the old beater with Sophie. I got the feeling she might also like a little space from Dad.

Alone in mediocre waves, on the least soulful surfboard I’d ever owned, I paddled into a knee-high peeler and was surprised by the simple pleasure of that board’s easy glide. I’d always sucked at cross-stepping, and hadn’t tried in 20 years, but I gave it a shot and walked right off the side of the board into a face-plant. That made me laugh, so I jumped back onto the board, sprint-paddled with that zippy glide back into the crowd, caught another wave and cross-stepped off the side, again.

On my third try, I managed a single step into the middle of the board, found the pocket on a slow two-footer and, without any advance warning, lost myself in the beautiful mystery known to surfers everywhere as trim. It’s hard to really define trim except to say that it’s a magic feeling borne of mating the perfect stance on a given board with the perfect line across a wave face so that everything flows without effort and you feel a momentary illusion of synchronicity with the cosmos.

Three seconds, 10 seconds – I can’t even guess how long I trimmed across that tiny blue wall. All I know is it didn’t matter and never had mattered, and once I paddled back into the crowd for yet another, my entire face was a big, out-of-control smile indistinguishable from those on the face of every other beginner. Because that’s what I was, a beginner.

At many surf breaks around the world, sharing is daring. In this scenario, it falls back into its more caring nature.

At many surf breaks around the world, sharing is daring. In this scenario, it falls back into its more caring nature.

Audrey’s skills turned solid so fast that all pretense of teaching faded, and we became just two people going surfing together. She even took over the job of strapping boards onto the roof rack while I filled jugs with hot water for the indispensable post-surf rinse. Nothing could beat all that, and I’ll still drop anything for an afternoon at the beach with that kid. But I’ve also been surprised by a change in my solo sessions, and my whole relationship to the water.

A friend heard about my cross-stepping aspiration and turned me onto one of the great old-time longboard shapers in Santa Cruz, Doug Haut, who made me a gorgeous 10’2″ noserider. Another friend insisted I borrow his 6’4″ round-nose retro fish, which is by far the smallest board I’ve had in 30 years. A few weeks ago, I took both to the beginner’s spot and spent the first 90 minutes taking cross-steps gingerly back and forth on the 10-foot log – still smiling like a freak – and then about an hour scooting around on that tiny fish like a kid on a skateboard, which made me chuckle uncontrollably.

Then I got a text saying Ocean Beach looked surprisingly big and good, so I drank a smoothie and sped up there, ran into a buddy’s garage and dragged out one of my old-dude guns. That buddy joined me in the paddle out – two old friends, way the hell offshore on 10–12-foot wave faces, having every bit as much fun as I’d had in the morning.

And sure, big Ocean Beach delivers an endorphin injection at a radically higher dosage than small Linda Mar. But now that I’ve got my head screwed on straight, the latter brings me an equally sweet shade of joy – on about twice as many days a year, with a much-lower bar to entry and all those happy beginners lifting my own mood every time.

As for Audrey, well, the foggy San-Francisco summer, plus a driver’s license and new teenage friends, have her temporarily distracted from the profound cosmic importance of surfing with her father. But the hot days of September and October are just around the corner, and I have no doubt she’ll be back.

In the meantime, I’m still working on that cross-step.

Daniel Duane is the author of Caught Inside: A Surfer’s Year on the California Coast and several other books. He lives in San Francisco and spends most of his non-surfing hours writing about climbing, surfing and other ways of enjoying this beautiful earth.