Natasha Woodworth, the designer behind Patagonia’s new backcountry ski touring kits, approaches skiing and technical design with the same understated competence.

Not that it matters, but the most talented skier at Patagonia is a gal named Tasha. You’ll never catch wind of that from her. You must either ski with her or ask someone to brag for her. I started with Linden Mallory, our Alpine product line manager, who’s no slouch himself. Sometimes you’ll hear someone else brag for him, too, about standing on the summit of Everest, among other radical endeavors he never mentions. But speaking on behalf of his ski partner, friend and colleague comes easily.

“Was up on Whitney skiing the Mountaineer’s Route with Tasha on a super windy spring day that never quite warmed up. It was howling winds and front points going up the couloir. At the col, the wind was whipping and when we were transitioning, wind caught one ski and ripped it out of her hand. It ran straight back down the couloir (the main Mountaineer’s Route) before doing a javelin-style stop in a wind swale about halfway down. Stuck right in by the tip like a lone arrow sticking out of the wall,” Linden begins.

Trip report searches on the route say it isn’t insanely steep, but it is steep enough that not many folks ski it, which Linden confirms. The first report that pops up features a center-staged quote: “Very moderate terrain after the Mountaineer’s Couloir.” Others tell of the exposure, the relative steepness that ends in cliffs—and they all say that the couloir rarely holds good snow.

“She didn’t just ski a few turns on a groomer on one leg (like ski racers do). She skied an exposed, bulletproof couloir at nearly 14,000 feet on one leg.”

On this particular day with Tasha, a friend of Linden’s from San Francisco (full of stoke, but not quite as solid a skier) down climbed the top portion of the couloir, given the exposure and the conditions that day: Steep, exposed and marginal, also known as “slide for life.”

“Tasha was standing there with one ski. She just shrugged and then on one leg, shredded down on one ski. It was insane, never seen anything like it,” Linden says. “She didn’t just ski a few turns on a groomer on one leg (like ski racers do). She skied an exposed, bulletproof couloir at nearly 14,000 feet on one leg.”

Then she grabbed her lost ski, clicked in, opened up into GS turns and ran it out. No big deal.

Making turns and testing new fabrics for the new Upstride and Stormstride Jackets and Pants, Tasha on the Villarica volcano in the south of Chile. Photo: Juan Luis De Heeckeren.

Making turns and testing new fabrics for the new Upstride and Stormstride Jackets and Pants, Tasha on the Villarica volcano in the south of Chile. Photo: Juan Luis De Heeckeren.

Talking with Tasha, that’s the feeling you get – that her skiing accomplishments are no big deal. A sign of modesty, yes, but also a sign of her pure love for skiing. None of it’s a big deal if you’ve got the heart for it.

The love started young in Tasha, around a year old, when her former ski racer parents (her mom was in the 1980 Olympics) put her on skis in Vermont where they lived. Family-shred eventually transitioned into the high school ski academy back East, Burke Mountain Academy. Academy students train on Burke Mountain’s seven steep, icy trails (accessed with one Poma lift).

“Ski academy high school is no doubt a privileged experience, but when I was there, the program was very humble and old-school,” Tasha says. “We would throw our roommates on our backs and run up hills for training; we didn’t have a gym like the kids in Tahoe – we did everything outside with what we had around us.”

Straight from the Natasha Woodworth Archive Collection: a shoebox. Tasha’s mom, Viki Fleckenstein Woodworth (pictured), sent this photo of her and a young Tasha skiing in Vermont. Photo: Dad, aka Richie Woodworth.

Straight from the Natasha Woodworth Archive Collection: a shoebox. Tasha’s mom, Viki Fleckenstein Woodworth (pictured), sent this photo of her and a young Tasha skiing in Vermont. Photo: Dad, aka Richie Woodworth.

Racing on the North American tour was an essential step, but for Tasha and the other Burke girls, the holy grail was always competing in Europe. “When we were training our coach used to always tell us that we were doing fine, but to expect dozens of other girls in Austria working twice as hard.” During high school, Tasha trained on European glaciers every fall and had the opportunity to work with the Austrian National Team. She describes the surprise of having her oxygen levels tested while on a treadmill and the very calculated, very European, very dialed systems and approaches to sport (and life). By the end of high school, many of the European glaciers were melting, so the US Ski Team moved training to Chile. “I was so focused on ski racing during that time,” Tasha says, “that I never really experienced the other big pieces of mountain culture in Europe.”

After fifteen knee surgeries, US Ski Team racing on the FIS Alpine European Cup, competing on the NCAA circuit while attending Middlebury College and two years working in the fashion industry in New York, Tasha found herself interviewing to be a Patagonia Sportswear designer. While working for Rebecca Taylor, Cynthia Rowley and Opening Ceremony, among others, her somewhat-disconnected New York ski life – sneaking away to Jackson to backcountry ski with friends or resort skiing back in Vermont – was becoming a sore spot. At Patagonia, although oceanside, not mountainside, there was relief to share the stoke for skiing and being outside. And the backyard Sierra Nevada.

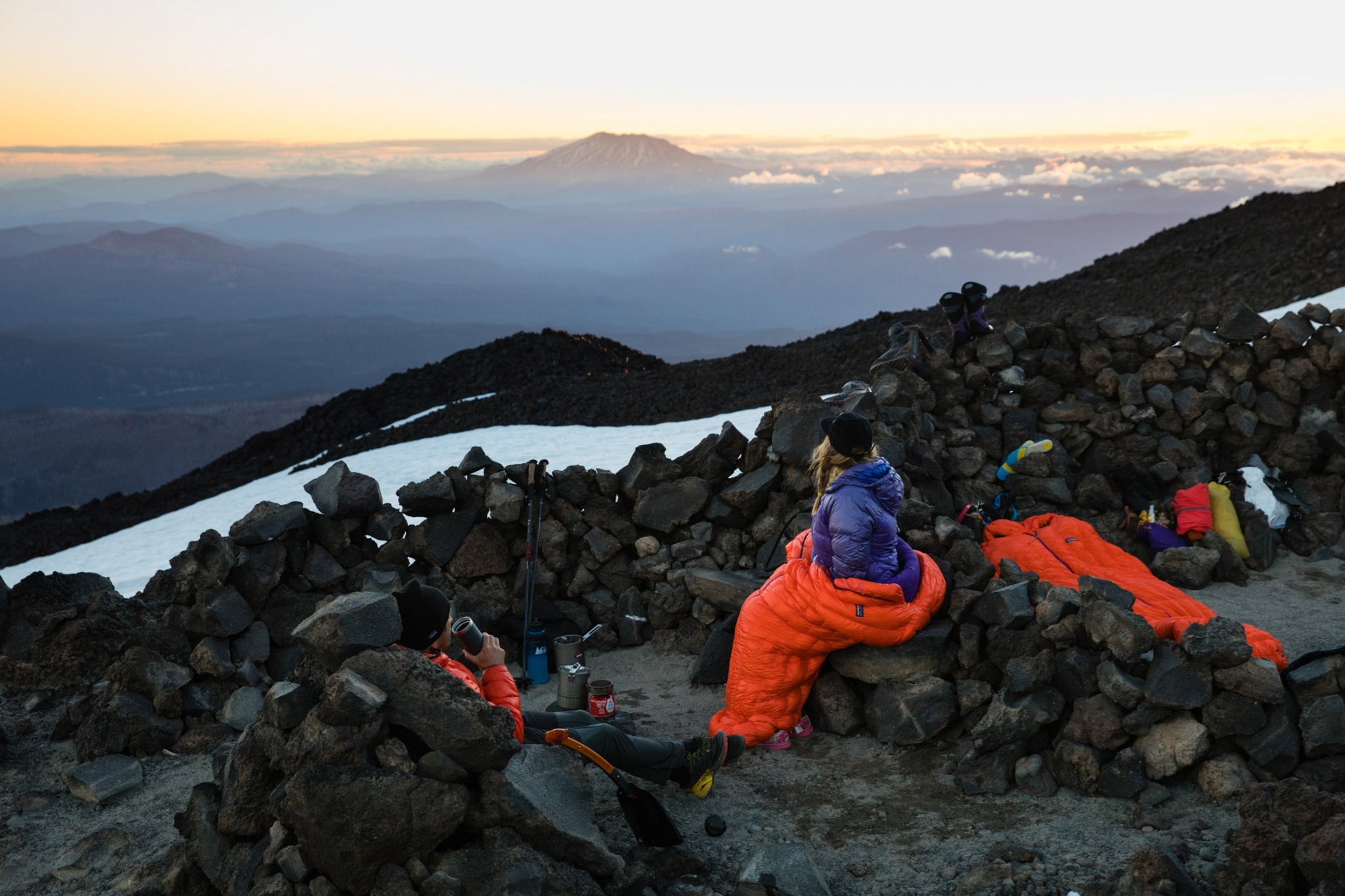

A night out with Tasha, and Forrest Shearer, in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, Washington. Photo: Tyler Roemer.

A night out with Tasha, and Forrest Shearer, in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, Washington. Photo: Tyler Roemer.

Tasha’s been a designer at Patagonia for seven years now, working full-time on the development of our technical products. She has attended ski mountaineering camps with Jackson-based Patagonia Snow ambassador Zahan Billimoria, driven the six hours up the eastern Sierra from our headquarters in Ventura for more trips than she can count and tested Patagonia products in mountains around the world. A few years ago, while starting work on this season’s new Upstride and Stormstride Jackets and Pants with our head of product innovation, Glen Morden, Tasha found herself back in Europe – this time without the GS skis.

With Glen she skied a nice little line, the Cosmiques, on her first day in the Chamonix Valley; he’d been hoping to get this run in condition for quite some time before their trip. “This was definitely a moment when I felt I had surely passed on the same passion and stoke toward our backcountry line that had led us to where we are today,” says Glen. “And because Tasha takes the same dedication from ski racing to learning about being in the backcountry to her approach in design, we knew the future of technical apparel at Patagonia was in the best of hands.”

Tasha took three years of Upstride and Stormstride prototypes around the world – most importantly, testing and validating them with those born and raised touring the Alps, where dawn patrols, hut-to-huts on the daily and lives nonchalantly lived around ski touring were the inspiration for the kits. The prototypes saw thousands of feet of elevation gain (and descent), sun, wind, rain, Euro, American and Canadian butts, and on one trip in Montana, three wolves, three foxes, two owls, one bear, one bison, one porcupine and one red-tailed hawk. The result was a couple of backcountry touring kits, handcrafted for the demands of going uphill and for peak-to-peak-to-peak-to-peak-to-peak tours when you might enjoy a café or a beer midday at the hütte.

“In Chamonix and parts of Austria, I finally got exposed to the ski touring scene in Europe,” Tasha says. “And really got to feel how much being observers of the mountains is part of the culture.” The consequences of backcountry skiing in the Alps can be big, and the skiers often seem casual because being in the mountains is so embedded in everyday life. To explain this culture rooted in mountain life, Tasha adopted a friend’s theory that Europeans have a different dynamic with mortality than North Americans because they live in the presence of thousand-year-old monuments and of the mountains – reminders that our lives are a blip in time.

Tasha in a moment of obsession while designing the Upstride and Stormstride Jackets and Pants. Tasha looked for new ways to place pockets for better mingling with a beacon, adjustments to the pants to accommodate a ski harness, the use of lighter trail running fabrics, plus interior materials that would make a jacket and pants comfortable to wear without baselayers—all with the discipline of placing only critical features, like vents and adjustable boot cuffs for integration with crampons and touring boots. She engineered articulation in the knee patterns a few degrees beyond our other snow pants to accommodate for precise and efficient uphill movement. Ventura, California. Photo: Kyle Sparks.

Tasha in a moment of obsession while designing the Upstride and Stormstride Jackets and Pants. Tasha looked for new ways to place pockets for better mingling with a beacon, adjustments to the pants to accommodate a ski harness, the use of lighter trail running fabrics, plus interior materials that would make a jacket and pants comfortable to wear without baselayers—all with the discipline of placing only critical features, like vents and adjustable boot cuffs for integration with crampons and touring boots. She engineered articulation in the knee patterns a few degrees beyond our other snow pants to accommodate for precise and efficient uphill movement. Ventura, California. Photo: Kyle Sparks.

This knowledge, along with everything else she’s been absorbing about snow science, is a shift from the skiing she knew as a young girl. “I was always in such a controlled environment, ski racing, so there’s a lot I am still discovering in the backcountry.” And that’s how the ski-lovers do it – they see it as a lifelong thing. Luckily for Tasha, she can make turns in crummy conditions just as easily as in the deepest of powder, with a fun-loving attitude on the side. For someone like her, there just aren’t many “bad” days on snow.

The other boasts start to come in. Accounts of watching her “straight-lining the chute with delicate and subtle little slashy course corrections” and “Maching out the apron and dropping all our jaws in the process.” There’s always the “geez, she knows how to ski.” But, even more important, there are the stories of her sincere love of skiing—the tales of not particularly great days, at not particularly exciting mountains and watching “Tasha lead the charge from what felt like bell-to-bell, so pumped. It was rad, reminded me of being in grade school when your whole crew was lapping the local hill, that was our scene that day and felt like it was Tasha ripping the heavy, wind-whipped pow, with a train of rippers behind her, smiling ear to ear, and it was like the best day ever.”

Banner image – “Tasha's attitude stands out more than her skiing to me,” says friend Max Hammer. "And it’s that attitude that has allowed her to become the badass that she is.” Tasha, caught in a moment before a smile, or badassery. Chamonix, France. Photo: Alex Buisse.

____________________________________________________________________

Author Profile