The road from the Princes Highway to Manyana runs along a ridge. It’s a single lane that snakes through what was – until earlier this year – some of the densest and most beautiful bushland on the South Coast of New South Wales. Now you can see straight through it. The vegetation was burned bare by the New Year bushfires and months later all that remains are charred trunks. Now one of the last remaining parcels of land adjoining Manyana – one that’s become a refuge for wildlife that survived the blaze – is set to be cleared by a Sydney developer to make way for a 182-lot housing development.

The blockade at Manyana, NSW. Photo: Max Zappas.

The blockade at Manyana, NSW. Photo: Max Zappas.

With only 521 permanent residents, the coastal town of Manyana is low-key, even by South Coast standards. Ulladulla is 30 minutes away. The nearest major employment hub of Nowra is 40. Before the bushfires, the area around Manyana was ringed by woodland, with birdsong echoing under the village’s thick canopy. Now, with the majority of that surrounding bushland ravished by fire, it’s hard to imagine anywhere that needs – or wants – a housing estate less than Manyana.

Jai Walsh, 26, grew up in Manyana. He spent his early years living in a caravan whilst his old man, Neil, built their family home on a plot of land he’d bought for $12,000. Jai describes an idyllic childhood: “It was perfect.” He’s slurping a cup of tea on smoko while working with his Dad, the pair are plumbers mainly servicing Bendalong and Manyana. “I had 10 mates all my age,” Jai recalls. “We’d surf and ride our bikes on the bike track we built through the bush. There was a dirt road in and out of town, and lots of the local crew survived on fishing and diving. It was a very pure existence back then.”

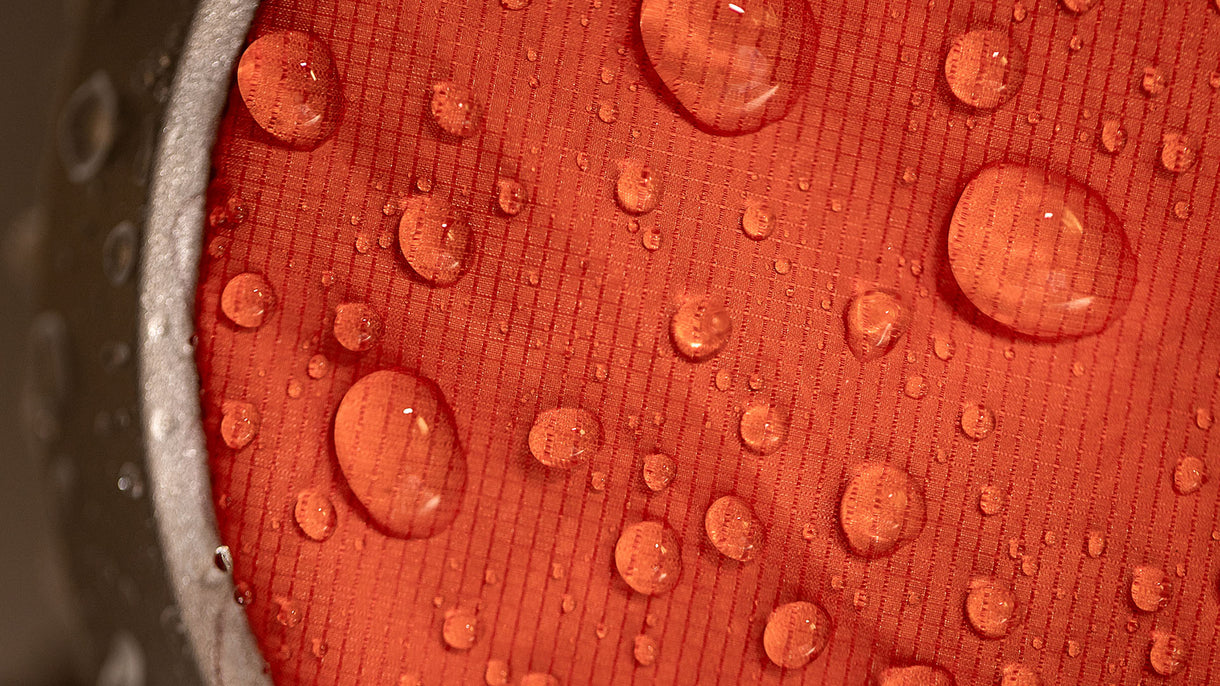

Only a small area of unburnt forest, and crucial wildlife habitat, remains in the area. Photo: Max Zappas.

Only a small area of unburnt forest, and crucial wildlife habitat, remains in the area. Photo: Max Zappas.

The development plans for the town date back almost 15 years, and Manyana locals are generally understanding about some construction in their area. Jai knows, “you can’t expect it to remain the same size forever.” What locals do want is a say, and for any developments to be reasonable in size and fitting with the community and the landscape. After all, that’s why anyone would want to move to Manyana in the first place.

“You’ve got to have some consideration for the fact it is a little quirky town,” Jai says. “There’s not a lot of work out here and most of the locals don’t earn much money. If you keep building holiday houses it keeps driving the house prices up, and eventually, the locals won’t be able to afford to live here. This is already happening.”

Having been fortunate to spend a lot of time with the Manyana community over the years, it doesn’t surprise me that they’ve got as far as they have in standing up against this development. All you have to do is spend a Saturday afternoon at the Manyana soccer fields to see how strong and full of spirit the folk down here are. How such a small village can field three teams with players ranging from 15 to 60-years-old every weekend still baffles me.

It also reaffirms that there’s something truly precious here and it’s worth standing up for.

Calls for the development to be halted upon leaves. Photo: Jarrah Lynch.

Calls for the development to be halted upon leaves. Photo: Jarrah Lynch.

The developer’s marketing campaigns don’t mention the fact that Manyana is only three-kilometres from Lake Conjola, where three lives were lost as 89 homes burned to the ground in the New Years’ fire. All the bushland surrounding Manyana burned except for the 20-hectare plot between Manyana and Cunjarong Point. This area is set to become Manyana Estate, a 182-lot development that, according to the ads, have been “selling fast”.

“That’s a lie for a start,” says Jorj Lowrey, a spokeswoman and a driving force behind Manyana Matters, a community group formed to save the bushland. “When I’d spoken to the developer, he’d sold 13 lots… and four buyers had backed out since the fires. So despite two-and-a-half years of advertising campaigns – full-page adverts in Sydney newspapers, TV commercials over Christmas, billboards – he’d sold 13 lots out of 182. “They can’t sell it, and maybe they’re using us to see if they can walk away with a tidy little profit from the coffers of government or council,” Jorj explains. “We really don’t care why they’re doing it; all we care about is that this land needs to be preserved and come hell or high water we’re going to make sure that happens.”

At the local soccer field, surfers use their boards to send a clear message. Photo: Max Zappas.

At the local soccer field, surfers use their boards to send a clear message. Photo: Max Zappas.

The campaign spearheaded by community group Manyana Matters is the reason the bush hasn’t been cleared already. It was originally due to be bulldozed in late May, before an on-site protest and media coverage saw that the bushland was granted a short reprieve. The movement soon grew, and this little South Coast town was national news.

“This land needs to be preserved and come hell or high water we’re going to make sure that happens.”

“This all started with making some phone calls to the council and the Department of Environment and doing some Google searches,” Jorj explains. “Developers will either hope something goes under the radar, or they’ll engage lawyers and throw all this money in the hope that you’ll back off – it’s bullying tactics, but the antidote is asking questions. Councilors and politicians are obliged to answer, that’s their job. If you have a problem, don’t take it to someone else to solve. Take it to the right person, ask the questions, and come up with a solution, not just the problem.”

There’s hope for Manyana. For locals still recovering from the Black Summer bushfires, the importance of the unburned bushland can’t be discounted. This bushland has become a last refuge for all sorts of animals, including endangered greater gliders and swift parrots. The Environmental Defenders Office, representing Manyana Matters, took a claim to the Federal Court and was successful in having the development referred to the Federal Environment Minister, where it will be scrutinised under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act.

“It’s bullying tactics, but the antidote is asking questions.”

Meanwhile, locals have turned the construction fencing that encircles the site into a statement of community solidarity. Artists have hung their work along the length of the fence and the area has become a rallying point for locals who’ve been gathering peacefully to mingle, hold yoga classes, and to keep this issue alive. Although the fate of the bushland is yet to be settled, what’s certain is that the Manyana Matters movement has become an exemplar of community activism in this country.

An area of NSW forest burnt out by the recent, unprecedented bushfires. Photo: Jarrah Lynch.

An area of NSW forest burnt out by the recent, unprecedented bushfires. Photo: Jarrah Lynch.

Perhaps Jerrinja Elder, Ron Carberry said it best during one of the rallies. “We’ve got to find balance between development, Aboriginal Culture, and the environment, y’know. We’ve got to come to some agreement between the government and the people so we can all have a say in these things. In these little towns, we’ve got so many people who love the environment, that if we all come together and fight together as one big family group, we’ll get more done.”