In 1897 the English author HG Wells wrote War of the Worlds, one of the first science fiction novels. Forty years later it was broadcast as an Orson Welles radio play and more recently as a Steven Spielberg movie. It's a story of the clash of two cultures: humans v Martians.

Wells claims the inspiration for his novel came from the invasion of lutruwita/Tasmania by the British, while critics of the day saw it as a statement on colonisation.

The Palawa had inhabited lutruwita since 'the beginning of time' and as animists understood that in order to survive in a place, they needed to be the custodians of that place. The two were intrinsically entwined. Imagine their sheer terror when aliens suddenly appeared out of the ether. Armed with advanced technology and an insatiable greed, it took the invaders less than 40 years to bring a culture of 60,000 years to the brink of extinction.

Even though they were hunter-gatherers, the Palawa footprint on the land was not without consequence. Fire was in their DNA and through eons of torching the place, reshaped the landscape to satisfy their needs. However, once they'd been overthrown and exiled, the landscape was suddenly reshaped to satisfy different wants.

The custodians had been replaced by future eaters.

Down here, if you're not a shade of green, you most certainly share a bed with someone who is. It's that sort of place. And that's understandable; after all it is the birthplace of the world's first Green party.

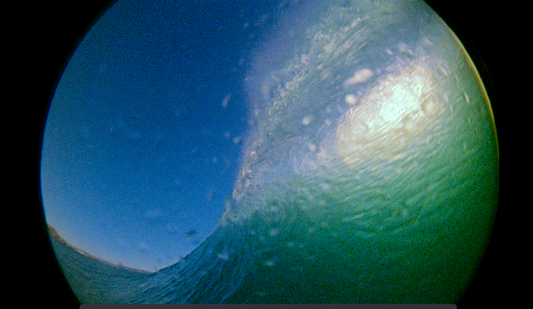

Unlike many of my mates, as a teenager I failed to answer the call to protest. Not that I didn't want to. There'd certainly been enough compelling causes – the flooding of Lake Pedder, the damming of wild rivers, the forest wars. But all I wanted to do was go surfing. I was basically a selfish hedonist and given I managed to live the surfing lifestyle for half a century, a bloody good one at that.

I supported my addiction by being a storyteller. A filmmaker and writer – producing stories on natural history, mining, forestry and Tasmanian Aboriginal culture. As a result I learnt a lot about the consequences of pursuing wants over needs, but true to my hedonistic bent, still chose to do nothing about it.

Trading my surfboard in for a kayak, shifted my focus from the ocean to the inland wilderness. Places where the environmental wars of my youth were fought. For the next decade I explored the southwest lakes and river systems, paddling to locations seldom visited. I got to see and appreciate, not only what a truly amazing place I lived in, but how much of it had been trashed since colonisation.

Then, I was offered a job as a wilderness guide at an exclusive camp at Port Davey in the far southwest. An area only accessible by a five-day walk, a journey of unknown duration in a boat, or 50 minutes in a light aircraft. Flying to my first camp I was blown away by the industrial scale of the salmon pens in the Huon River and D'Entrecasteaux Channel. It was my 'light bulb' moment, inspiring me to join Surfrider Tasmania, and a cohort of community groups called TAMP (Tasmanian Alliance for Marine Protection).

Suddenly I'd become a salmon activist.